1979: A descent into chaos

25. July 30, July 31, August 1, August 2, 1979

1979 begins a sort of opening out of the football kicking strips. They have always been a two person operation between Charlie Brown and Lucy. They have always taken place on one day, with no lead in or follow up strips; they have always appeared on a Sunday. They could stand alone. Not in 1979.

In 1979, the actual attempt to kick the football develops over four daily strips, from July 30 to August 2. There is also a long setup this year, a story that starts on July 3 (!) during baseball season (!) when Charlie Brown suddenly feels "kind of woozy" on the pitcher's mound. Lucy walks in from right field and says "You've probably been hit on the head with too many fly balls." Things escalate quickly from here. Charlie Brown goes to the "Ace Memorial Hospital" Emergency Entrance by himself because his parents are "at the Barber's Picnic" (July 9). We are never told, and neither is Charlie Brown, what ailment he has. On July 14, he says "I wonder if I'm dying . . . I wonder if they'd tell me if I were dying . . ." as he lies in bed. He continues in the next panel, " I wonder if they'd tell me if I'm not dying . . . maybe I'm already dead." You are not dead Charlie Brown. The next day he seems to have escaped his dread, as he calls himself "Joe Patient." Except for a brief appearance in the first panel on July 22, we do not see Charlie Brown again until Sunday, July 29 when he returns home and greets Snoopy. July 29 also reminds us of one of

Peanuts' best running gags--Snoopy does not know Charlie Brown's name. He stares, from the top of his doghouse as Charlie Brown talks to him. In the final panel, Snoopy thinks "Now I remember! He's that round-headed kid who always feeds me. ." (There are two dots after this thought--neither the full-stop of a period or the gesture toward continuation of ellipses.) Snoopy here reminds me of the narrator of Kafka's "Investigations of a Dog" (which becomes a really interesting story if one imagines that Snoopy is the actual writer of the story, but that is for a different post), whose investigations center on "the question [of] what the canine race nourished itself upon." Unlike his fellows, Kafka's dog seeks to know where his food comes from. Snoopy has his own personal answer; it comes from the round-headed kid. Anyway, the two weeks of July 1979 when we do not see Charlie Brown (except for the one panel on July 14 as noted above) focuses on how his friends respond to his hospitalization. Sally, his sister, feeds his dog, but also moves into his room. Marcie and Peppermint Patty are denied a visit to Charlie Brown because they are two young. They instead sit on a park bench outside the hospital, upon which Marcie confesses her love for Charlie Brown and even says "In fact, if he asked me, I'd even marry Chuck!" Peppermint Patty then tries to check Marcie into the hospital for being "sicker" than Charlie Brown.

But what about Lucy? What does Lucy do when she finds out that Charlie Brown is in the hospital? Her first response, when Linus tells her that Charlie Brown is in the hospital, on July 16, is "I'm glad it wasn't me!" She says this with a frown, her elbows perched on the small brick wall that the characters often converse at, her hands at the side of her frowning face. A few days later, on July 19, she is crying on Schroeder's piano. "He's got to get well! He's got to!

OH, BOO HOO HOO HOO! SOB!" Schroeder nonchalantly responds to her emotional outburst by saying "It's interesting that you should cry over him when you're the one who always treated him so mean!" Does Schroeder think Charlie Brown is dead? Why does he use the past tense? He does not seem too concerned, as he then tells Lucy "And stop wiping your tears with my piano!" Everybody has their own obsessions. It is just under five months until Beethoven's birthday. Almost a week later, on July 26, Lucy tells Schroeder that she "can't eat or sleep" because she's so worried about Charlie Brown. Lucy is traumatized by Charlie Brown's continuing illness. She lashes out. "Maybe I could send him a threatening letter" she says, as Linus rolls his eyes. Two days later, at home, Linus tells her "I just talked with Charlie Brown's mom . . . He's not any better." Maybe Lucy briefly, or even unconsciously, remembers telling Charlie Brown in 1975 "I'm not your mother, Charlie Brown!" Mouth agape, arms thrown in the air, Lucy has a three panel meltdown. "What's wrong with a world where Charlie Brown can get sick, and then not get any better?" Lucy cares deeply for Charlie Brown. Maybe, Lucy loves Charlie Brown. This month of strips should be read by anyone who complains that the kids in

Peanuts are mean and cruel to each other, and especially to Charlie Brown. They might be, but a sense of belonging and togetherness underlies the meanness and cruelty. They know each other; they are friends; they play out the same routines year after with love. Lucy returns to form in the last panel. With a fist raised and sweat flying from her face, she exclaims through an open mouth and clenched teeth "

I NEED SOMEBODY TO HIT!!," with the word "hit" nearly the size of her head.

July 27, though reveals the true depth of Lucy's caring for Charlie Brown. In the first panel, Lucy stands outdoors, solitary in a pitch black night. She is in what Maurice Blanchot, in

The Space of Literature, calls "empty night," a space of darkness beyond "the first night" of mere darkness and sleep. It is the paradoxical appearance of "everything has disappeared" experienced in the first night. Lucy, in her desperation, meets this appearance of disappearance, embodied by "apparitions, phantoms, and dreams" with a finger raised and a promise to Charlie Brown. She sees what she fears most--the apparition of Charlie Brown's foot connecting with the football, the dream of the smile on his face when he finally kicks the ball. And Lucy is willing to endure this darkest night for Charlie Brown. Panel two of the comic draws in on her solemn face; we can no longer see the ground, only the black space behind her head. Her eyes are shut in straight lines; her mouth is a small oval, as she raises her right hand and says "If you get well, I promise I'll never pull the football away again!" The repercussions of this promise will echo forward through every strip that follows for the next twenty years. In panel three, Linus walks out of the darkness into the frame and tells his sister "That's quite a promise" With this statement, Linus has become part of the football-kicking routine. He will serve as guarantor of this promise. He has notarized it. The next day, on July 28, Linus asks Lucy to confirm her promise in the mundane light of day. As she sits in her beanbag in front of the television, Lucy once again raises her right hand and confirms "That is my solemn promise!" The very next day Charlie Brown is home; he spends this Sunday strip talking to Snoopy. The beginning of the reckoning will start the next day.

On July 30, Lucy, reclining in her beanbag in front of the television, hears a "KNOCK KNOCK KNOCK" at the door. In the third panel, she opens the door to Charlie Brown's smiling face. She exclaims "Charlie Brown! You're back!! You're well!" Her late-night promise has worked and her happiness at Charlie Brown's return is about to turn into something else. Noticeably, we can only see Charlie Brown and Lucy from the chest up; we cannot see their hands. Panel four takes a wider perspective, and we can see that Charlie Brown is lightly tossing a football up with both hands. His illness, and Lucy's despair at it, are now forgotten. He turns away from her and says over his shoulder "I heard something about a promise . . ." Lucy can only respond with a frown and an "Oh, good grief!" as they both stand on her front porch. Linus has told Charlie Brown about Lucy's promise. But this is not a Sunday strip, so we are left with this scene for a whole day, with the football, Charlie Brown, and Lucy all poised, frozen in the moment before they walk to the grass where the football kicking will take place.

July 31 shows us that Linus has indeed taken an interest in Lucy's and Charlie Brown's routine. He stands on the left side of the first panel, as Lucy, in the middle, kneels and holds the football. Charlie Brown, on the right, points at the football and says what Lucy usually says. "You hold the ball, and I'll come running up and kick it" He does not even need an exclamation point. Lucy stares at the ball. In the second panel, Charlie Brown, in profile, eye closed and finger in the air reminds Lucy of her promise. As he turns and begins walking away from the football in panel three, Lucy, holding the football in both hands, not yet ready to place one end of it on the ground and balance the other end with her finger, asks "Can't I change my mind?" Charlie Brown, once again without an exclamation point, says as he walks, "No, you can't break a promise to a sick friend" Lucy cannot deny her promise and she cannot deny her friendship. Charlie Brown walks off panel and Linus exclaims "Ha!" at his sister, as he asks her what she is going to do. She responds "Quiet! I'm thinking!" She is in trouble. She will not renege on her promise and she has no plan. She has no document, no banana, no sunglasses. She has no verbal weapons to throw at Charlie Brown, no appeals to her innocence, no tears, nothing. She still holds the football in both hands, reluctant to tee it up.

On August 1, she has given up. The football is ready to be kicked. Charlie Brown continues to walk away from the football, with Linus right behind him. Charlie Brown says "This time I'm really gonna kick that football. He is resolute. His hands in front of him, he looks like he is about to clap in anticipation. As if Charlie Brown's doubt cannot be fully erased, Linus embodies it and gives it voice. "You're crazy Charlie Brown! She'll pull it away like she always does! Don't trust her!" he says, his arms spread wide. Charlie Brown must recognize these words as his own from years past; nonetheless, he responds to Linus by spreading his own arms out wide and simply says "But she promised she'd never pull it away again if I got well . ." He starts to run toward the football with confidence. "I feel great! Here I go!!" He voice no hyperbole--he's not going to kick the football to the moon or out of the universe; he is just going to kick it. Charlie Brown, as he always has, trusts Lucy. In the background, Linus covers his eyes and says "I can't look. ." Which is stronger? Charlie Brown's faith in a promise from a friend? Or Linus' doubt of his sister (a doubt, of course, that is well-earned by Linus)? Spreading the routine over four daily panels raises the tensions and the stakes. I cannot even imagine what it was like to read these comics in 1979 in a newspaper. Did the world come to a stop on August 1st? Were people waiting at their doorsteps for the daily paper to arrive early on the morning of August 2? I might have read these strips in the newspaper; I was eight years old in 1979 and I know that I had been reading

Peanuts. I do not remember, though, maybe I was only reading the paperback compilations I checked out of my school library.

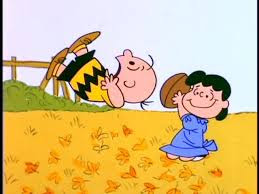

August 2, 1979. Lucy, her head framed by three fluffy clouds, kneels in the center of the frame, one end of the football on the ground, one end held by her finger. She looks off to the right and we all know what she sees. The look on her face seems to say that she cannot pull the football away and that she cannot believe that she cannot pull the football away. While every comic panel is a static image, this particular panel seems frozen in time, stuck in the moment before anything happens. And then chaos. Panel two makes no sense, like a hieroglyphic without a Rosetta stone. In the lower left corner, Charlie Brown swings his leg into the air. The football is somehow behind him. Lucy is flying through the air over Charlie Brown's head, feet facing upward, her screaming "

AAUGH!" filling the upper left quarter of the panel. The expected recurrence of Charlie Brown flying through the air, of the football being pulled away by a kneeling Lucy is missing. Its absence denotes its choreography--the curving lines tracing Charlie Brown's ascent echoed by the smaller curved lines of the football as Lucy pulls it away from his foot. Here there is just chaos. Charlie Brown does not ascend; his foot only kicks up to the level of his chest. Lines radiate out from Lucy in three directions. The disjunctions of this panel make me nauseous. . . Panel three offers explanation but not resolution. The football sits unmoving on the ground in the background. Charlie Brown sits on the ground next to it with a "?" to the left of and slightly above his head. He looks stunned as he sees Lucy in front of him, her head turned back, her mouth agape, her right hand held in her left, as she screams, surrounded by stars, "My finger! My hand! my arm!" She dances in pain. Her words fill the top half of the final panel. "You missed the ball, you blockhead! You kicked my finger! You kicked my hand!" In a smaller speech bubble below this, she screams "Ow! Ow! Ow!" The football lies on the ground, and Charlie Brown sits next to it; he looks down at it with another "?" and a chagrined look. He is tiny in the background, barely taller than the signature "Schulz" that runs up the right edge of the panel next to him. Lucy has kept her promise. She did not pull the ball away. Charlie Brown missed the football and kicked Lucy's hand. On August 3, she says "I kept my promise, didn't I? I didn't pull the ball away" Charlie Brown agrees. We see Lucy's right arm encased by a gigantic cast. Why did Charlie Brown miss the football? Was it an athletic failure, akin to his striking out with the winning run on base in the bottom of the 9th? Was it more of an inevitable turn, like his kite finding its way into the kite-eating tree? Did he miss on purpose, to keep the routine alive? Who knows? What was Charlie Brown sick with? Did Lucy's promise cure him? Have we witnessed a miracle? Is Lucy halfway to becoming a saint? Is Charlie Brown? Is John Coltrane?