1. How I Read How to Read Nancy

The heart of Paul Karasik’s and Mark Newgarden’s How to Read Nancy: The Elements of Comics in Three Easy Panels comprises forty-four numbered, detailed, nuanced close readings of Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy strip from August 8, 1959. From my perspective as a professor of literature trained in both literary theory and close reading, these analyses astound me in their depth and breadth. Like many excellent close readings, Karasik and Newgarden start with a seemingly simple text: a three panel, black and white comic strip that contains only three words repeated three times. They start with a “look at the strip, the whole strip, and nothing but the strip” (73). Each numbered reading has three sections; “Context,” “Text,” and a short, one sentence “Moral.” The readings are color-coded by section; for instance, numbers 2 through five are marked by a green rectangular box that contains the words “The Script” on the left side page. Each number, in turn, focuses on a detail of the script, so that 2 is titled “The Gag;” 3 is “The Last Panel;” 4 is “Dialogue;” and 5 is “Balloon Placement.” Other sections include “The Cast,” “Props & Special Effects,” “Production Design,” “The Cartoonist’s Hand,” “Details, Details, Details,” “The Reader,” and a final return to “The Strip (Again).” Each of these sections contains differing amounts of numbered readings. “Production Design” takes up readings 17 through 21; “The Cartoonist’s Hand” contains readings 33 through 37.

Taken together, these readings establish just what kind of comic genius Bushmiller was. He was a master of the line, of pacing, of gesture, of economy and detail. More simply, he was a master of the gag, of what he called “the snapper.” Karasik and Newgarden write, “The pursuit of the Perfect Gag (‘the one which will knock everybody dead’) clearly became the raison d’êtrefor Nancy—and for Bushmiller himself” (62). Their book shows how Bushmiller achieved what he wanted. After reading How to Read Nancy, one would be hard-pressed to argue with the assertion that Bushmiller was the master formalist of the gag comic strip—no other comic creator comes close. (I would claim that Charles Schulz is the only other genius of the comic strip, and a more nuanced and wide-ranging one at that, but Bushmiller and Schulz are so different in their work that the comparison is unfair to both of them.)

One might argue that a reader only needs access to Bushmiller’s strips to see and appreciate his genius. While this may be true, it is also true that Karasik and Newgarden teach readers how to see and appreciate even more in Nancy. Literary critics often note that so-called “difficult” books like those by Gertrude Stein or James Joyce are best understood through the lecturing, discussion, and close reading that takes place in the classroom. How to Read Nancyteaches readers that Nancy’s simplicity belies its complexity. One can learn a lotby slowing down, and slowing down in a serious way. Instead of taking the few seconds that it takes to read a typical comic strip, Karasik and Newgarden ask readers to dwell for hours, days, weeks, thinking about one Nancystrip. That dwelling pays off.

Let me give a few examples of what their close reading reveals. “4. Dialogue” illustrates how the differing placement of the strips only words “DRAW, YOU VARMINT” on the right or left side of each panel guide reader’s eyes through the strip. As they note Bushmiller’s familiarity with television Westerns of the 1950s, Karasik and Newgarden note, “Bushmiller, always working with the iconic, invoked the precise three words and four syllables that gave him what his gag needed—no more and no less” (79). Their discussion of “5. Balloon Placement” is no less elucidating. The speech balIoon appears in the upper-right corner of the strip’s final panel, so that “the rhythm pauses a beat. When the reader and the third balloon finally meet, it is at the outermost extreme . . . The payoff comes from reading the same line of dialogue a third and final time afterencountering a very different image than what we have been conditioned to expect” (81). This reading leads Karasik and Newgarden to the moral “In the design of comics, situating the text is primary” (81).

The authors pay just as much, if not more, attention to the visual aspects of the comic. Their close readings serve multiple purposes. Readers do indeed learn “how” to read Nancy. We also learn about the craft of comics writing, the nuts and bolts that we don’t see in a finished strip. And, we learn, from Karasik and Newgarden’s example, how to do close readings. The attention they pay to small visual details such as “17. The Horizon Line,” and “19. The Fence” show what readers can gain from close, focused, looking at and thinking about the seeming mundane details of a text. They note that Bushmiller does not include “cross braces” on the fence even though they should realistically be there, because “to include the cross braces on the inside of this fence would disrupt the visual flow that Bushmiller establishes here with its linear vertical repetition” (109). As a reader of texts, I love this level of attention. I could go on for pages with more examples—the way they write about negative space, about gesture, about motion lines, about panel size, all with the same brilliant concentration on the words and images on the page. All of these close readings add up to give voice to the “deep poetry” of the cartoonist’s “language exemplified by the clear, unambiguous example of Ernie Bushmiller” (158). Karasik and Newgarden offer ample evidence that Bushmiller’s achievement is singular in the 20thcentury.

Perhaps what is most impressive about their close reading lies in the fact that it is not exhaustive. More could be said about this specific Nancystrip. And one could do such close reading of nearly any of Bushmiller’s Nancys. Karasik and Newgarden’s close reading opens the world of Nancyto a multitude of other detailed readings. There will always be something more to say about Nancy.

I have focused so far only the “reading” part of How to Read Nancy. While their long close reading makes up the bulk of the book, Karasik and Newgarden sandwich their reading with a critical bibliographic essay called “How to Read Nancy?” and a series of appendices that show Bushmiller’s inspirations in everyday objects and architecture, context for his gags, discussion of the ways that different newspapers laid out comic strips, the strategies Bushmiller used in longer Sunday strips, and pages and pages of Nancystrips that illustrate things including Bushmiller’s use of white space, his balloon design, his use of punctuation, and panel gutters.

The bibliographic essay is especially welcome, as the authors note that Bushmiller “was a man of few words [who] left behind remarkably few interviews, press items, and written works” (9). Karasik and Newgarden create a vivid picture of how Bushmiller got his foot in the door at the New York World by doing hackwork like drawing (!) crossword puzzles and illustrating brain teasers. Bushmiller, thanks to the connections he formed at the Worldwas able to publish his first comic when he was fifteen. Bushmiller seemed to have lived an idealized 20thcentury life. Karasik and Newgarden write the Bushmiller and his wife Abby “were best friends as well as partners [who] enjoyed a marriage that worked for over half a century” (52). The Bushmillers moved from the Bronx to the suburbs of Stamford, Connecticut in 1951 (63). The authors describe the Stamford house as such: “Their Stamford home was large and comfortable and decorated with the work of contemporary American illustrators . . . The rambling grounds offered ample foliage and wildlife . . . A small grouping of rounded white rocks cropped out from the closely trimmed world outside his studio window” (64). Here, and in the studio he kept in New York, Bushmiller dedicated his life to creating Nancy. We are all the better for it.

But. Something about this biographical essay makes me uneasy. I fully admit my unease is no concern of the authors and is outside the purview of the kind of book they have written. But. I do wish at least a small gesture had been made to the systemic white privilege of 20thcentury America that provided the soil for the blossoming of Bushmiller’s talent. (I did mention I was a literary theorist in the first paragraph of this review.) The pictures of Bushmiller and his colleagues that appear throughout the essay universally show groups of white men. Look, for instance, at the picture of the “Art Department of the ‘Sunday World’” on page 32. I count twelve formally-dressed white men at their drawing boards. Karasik and Newgarden cite Leo Kober, a Sunday World Magazineillustrator, describing the workplace environment of the art department. “Art enchained into two columns and three columns, veloxes and silverprints, comics, pretty girls and cartoons . . . done by men devoted to a great and wonderful passion” (34, ellipses in original). I don’t think the pretty girls were creating cartoons. Karasik and Bushmiller quote a Bushmiller neighbor who said that Bushmiller’s wife, Abby, “was the ideal cartoonist’s wife, attuned to the rhythm of and heartbeat of his work . . . but she also knew when to give him space” (52). Another Bushmiller colleague notes that Bushmiller “never had children. . . I’ve been thinking about cartoonists, and I know there are a few exceptions to this . . . but they had either very, very small families—or no families. It was almost a characteristic of the business. Either the woman becomes part of the operation or it falls apart” (52). Here, we are firmly in the mythos of the singular, white male genius, working away in his study, insulated from the everyday cares of the world.

Bushmiller was a formalist. Besides some propoganda during World War II, Nancycan be read as an insular work, cut off from the world. Karasik and Newgarden quote Bushmiller as saying “I have never gotten an idea from real life” (62). They add, “Emotional depth, social comment, plot, internal consistency, and common sense were all merrily surrendered in Bushmiller’s universe to the true function of a comic strip as he now unrelentingly saw it” (62). The connection between his idyllic life, and his ability to become a formalist by not worrying about his place in the world might have been made explicit here, instead of remaining implicit.

This is not to say that Bushmiller is not a genius. His 22,000 strips are a singular accomplishment. As Karasik and Newgarden put it, “few cartoonists ever provided such a dependable public utility for so many years” (63). They write elsewhere, “We like Nancy. A lot” (23). In How to Read Nancy, they make this clear. I like Nancy a lot, too. I like her more after reading How to Read Nancy.

2. Addendum: Rejecting the Cult of Bushmiller

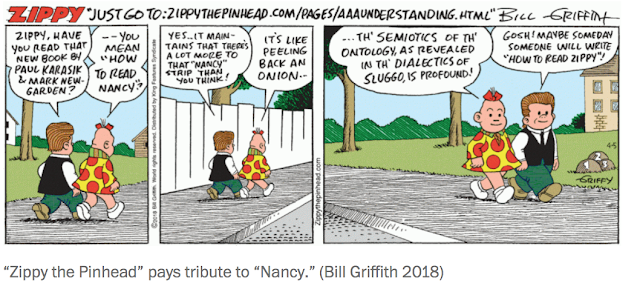

In the review above, I note that one might see in How to Read Nancyan inattention to social representation, cultural norms, and systemic practices. I’ll just say it. Ernie Bushmiller had to be a white male or he would never have become Ernie Bushmiller, creator of Nancy. This point is obvious, and is not meant as a critique of Karasik and Newgarden’s book. But it does point to the one thing I don’t like about How to Read Nancy, and it’s not really the fault of Karasik and Newgarden. I see How to Read Nancyas an after the fact manifesto of the cult of Bushmiller, or “Bushmillerites.” Bushmillerites seem to be mostly white middle-aged males (true story: I’m a 47-year old white male). The names are familiar: Art Spiegelman, Chris Ware, Daniel Clowes, Bill Griffith. A quick tangent. Griffiths has done amazing work incorporating Nancy and Sluggo into his Zippy the Pinhead. He brings things full circle in this recent strip.

Jaimes has noted that she is inspired by memes and this panel should be in wide circulation. I've written on this blog about how I think Jaimes is funny and on how Bushmiller himself focused on the technology of his time (telephones, records, television). In this addendum I want to address a different point.

To be blunt again: Many of the Bushmillerites fetishize Aunt Fritzi in some creepy ways, inspired by Bushmiller panels like this one. (Again, do some internet searches if you don't believe me.)

Besides her pearl earrings, Fritzi is remarkably less formal. She wears a blue t-shirt and her hairdo is a bit simpler. She is also not so large that she has to lean into the frame. She also seems to have lost interest in sending Nancy to the corner or beating her. In the Bushmiller years, Nancy would only get away with a smart aleck comment in the first panel.

Fritzi declutters her office on June 5 and tries a new hairstyle on June 6.

Fritzi with Nancy's hair in the last panel is hilarious. And Jaimes brings home the idea of a new, non-exotic Fritzi on June 7.

She has donated her "old outfits" which we are clearly meant to read as her 1940s-era formal skirts and dresses. Meet the new Aunt Fritzi. She wears athleisure wear. (Let's all try to forget the t-shirts Guy Gilchrist gave her.)

Jaimes has brought another update to Nancy. In How to Read Nancy, Karasik and Newgarden write that in the early 1970s “Bushmiller found himself under increasing editorial pressure from his syndicate to introduce a black youngster into his insular cast. In a widely printed 1973 article on this issue by Associated Press reporter James Carrier, the cartoonist came across as sensitive (yet ambivalent): ‘My instincts tell me to do it. I’m waiting . . .’ His private concerns were, according to Al Plastino, far more characteristic: ‘Black kid? Where’s the gag?’”

Of course, a "black kid" could just be a kid in Nancy because black kids exist. Karasik and Newgarden follow up the discussion of a black character in Nancy by writing about Bushmiller's cast of characters. “By keeping his cast small and familiar Bushmiller kept one aspect of his strip absolutely predictable to his daily readers—an important consideration given the often surreal bent of his visual humor. ‘I think I have an instinct. I can smell and taste the average American” (86). Putting these two quotations together draws a line between "black kid" and "average American." I'm sure this was unintentional, but I'm also sure that Jaimes is more interested in representing different kinds of people.

Nancy's classroom is less crowded than it was in the Bushmiller days and it is also less white.

I like Bushmiller's Nancy. I like Jaimes' Nancy. I like Gilchrist's Nancy.